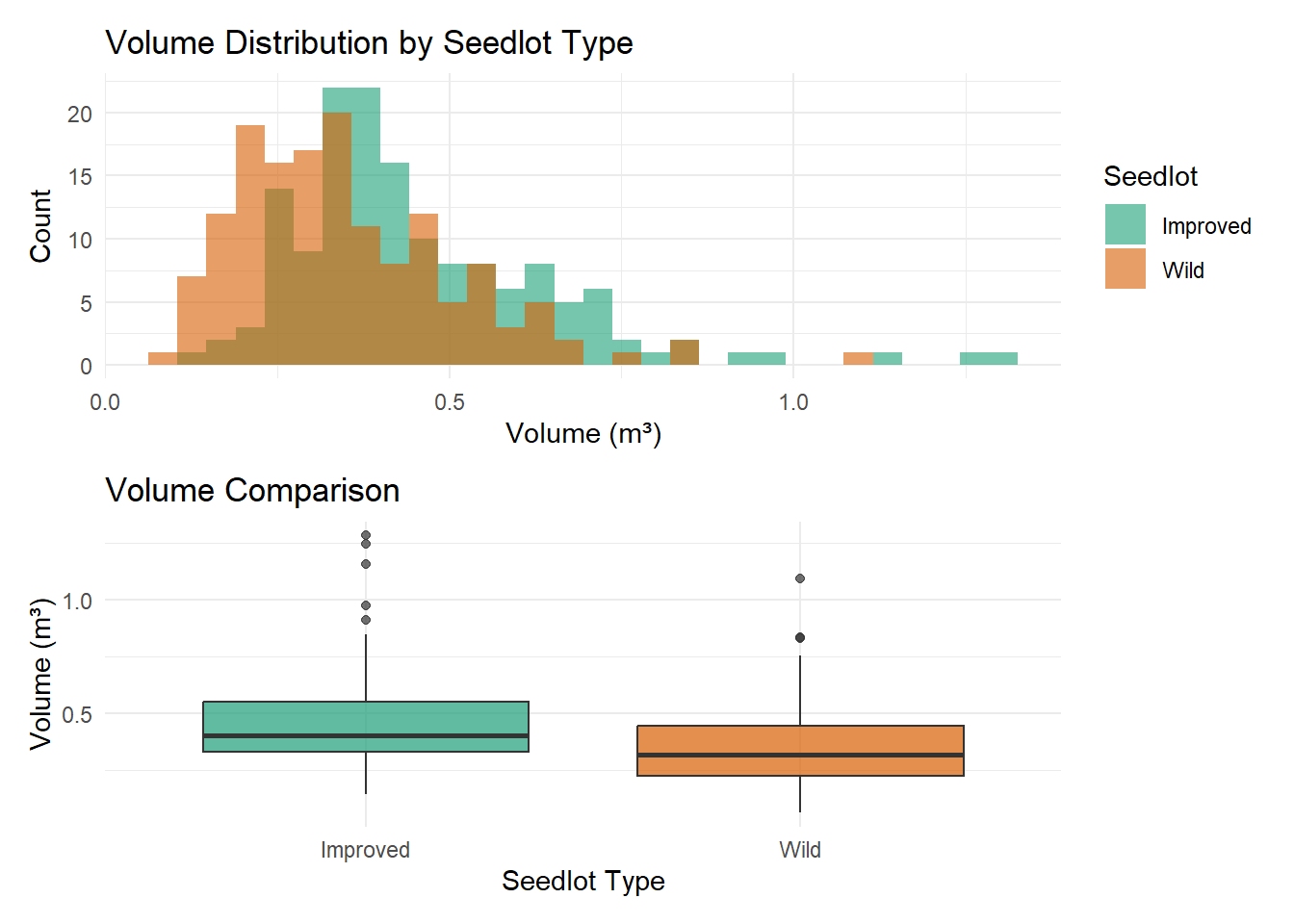

Alberta forest companies face a multi-million dollar question: Should we invest in tree improvement programs? The challenge isn’t biological – field trials consistently show 10-25% volume gains from improved seedlings. The challenge is that government recognizes only a fraction of demonstrated gains for regulatory purposes.

In Alberta’s Forest Management Agreement (FMA) system, companies lease harvesting rights on Crown land. To access additional timber volume from tree improvement, they need government approval to adjust their Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) – a mechanism called the Allowable Cut Effect (ACE).

The reality: As of 2016, seven Controlled Parentage Programs (tree improvement programs) existed in Alberta with government-approved height gains averaging 2.3% – far below the 10-25% demonstrated in field trials. Of these seven programs, only three companies found the economics compelling enough to incorporate the gains into their Forest Management Plans.

Why did the other four companies decline? With only 2.3% recognized gains, the return on investment becomes marginal. When you’re investing millions in breeding programs, seed orchards, and improved seedlings at $2.50 each (vs. $0.50 for wild seed), the economics only work if enough factors align favorably: high deployment rates, manageable costs, good survival rates, favorable markets.

From industry’s perspective (Schreiber & Thomas, 2017): “The low levels of genetic gain and its translation into the desired ACE, the long timelines for TI program development (i.e., decades), and the lack of certainty and risk aversion with Government approvals do not justify the expenses involved.”

Why Standard Cost-Benefit Analysis Falls Short

Schreiber & Thomas (2017) developed an economic model (TIIFA) for Alberta tree improvement programs. Using sensitivity analysis across different scenarios, they showed that investment can be profitable even with modest gains – but profitability depends on multiple uncertain factors aligning favorably.

Their key findings:

- With 2% volume gain per decade and deployment reaching 15%+, investment is profitable at 8% discount rate

- Deployment area matters as much as genetic gain: Increasing deployment from 5% to 20% per decade has enormous impact

- Program costs are manageable: Even at $5 million per decade, programs can be profitable

- Discount rate is critical: NPV strongly positive at 4%, moderately positive at 8%, barely positive at 12%

But their model analyzed scenarios independently. In reality, companies face compound uncertainty:

- Will we achieve 15% deployment rates across our FMA area? (Operational)

- Will program costs stay under $5M per decade? (Financial)

- Will the 2.3% recognized gains actually translate to field performance? (Biological)

- What will stumpage fees and lumber prices be over the 20-year FMP cycle? (Market)

- Will climate change affect realization of genetic gains? (Environmental)

Their conclusion: “Investment in TI still remains a profitable enterprise... if the area planted is maximized on which improved seed is deployed.”

That “if” is doing a lot of work. When four out of seven companies look at the same analysis and decide not to incorporate gains into their plans, they’re implicitly saying: “We’re not confident enough that the conditions will align favorably.”

Standard economic models give point estimates under assumed scenarios. What companies actually need to know: “What’s the probability our investment will be profitable given simultaneous uncertainty across all these factors?”

Government faces similar challenges. Regulators must balance economic benefits (forest industry jobs, community sustainability) against conservation of public forests. When field trials show 10-25% gains but regulators approve only 2.3%, this conservatism reflects genuine uncertainty: Will gains materialize at scale across diverse sites? Will deployment rates be sufficient? A Bayesian framework could help regulators make more transparent, defensible decisions by quantifying: “At 80% confidence, we expect gains between 1.8-2.8%; approving 2.3% AAC increases keeps risk of over-harvest below 10%.” This provides accountable stewardship of public resources while supporting industry investment.

The Bayesian Advantage

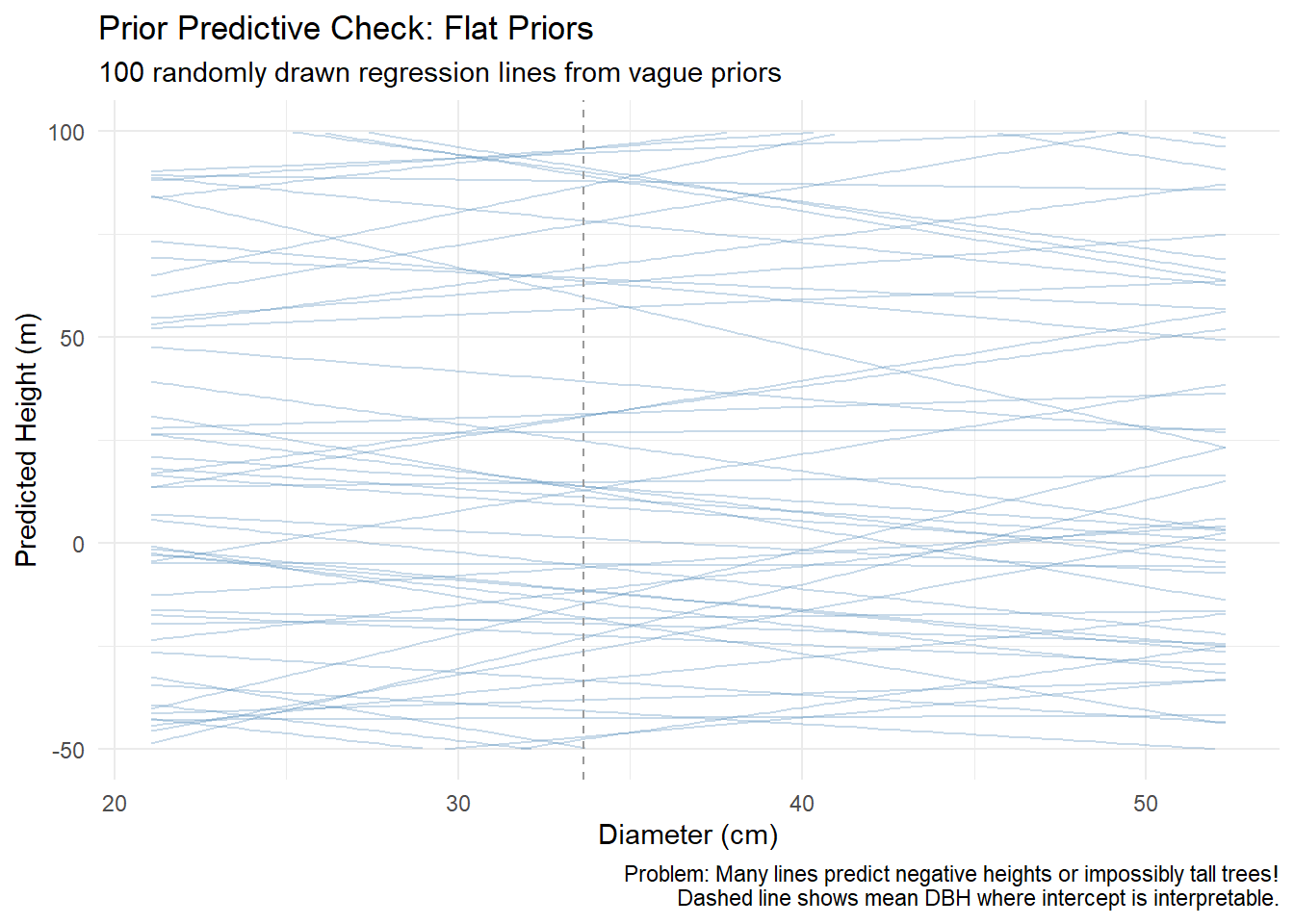

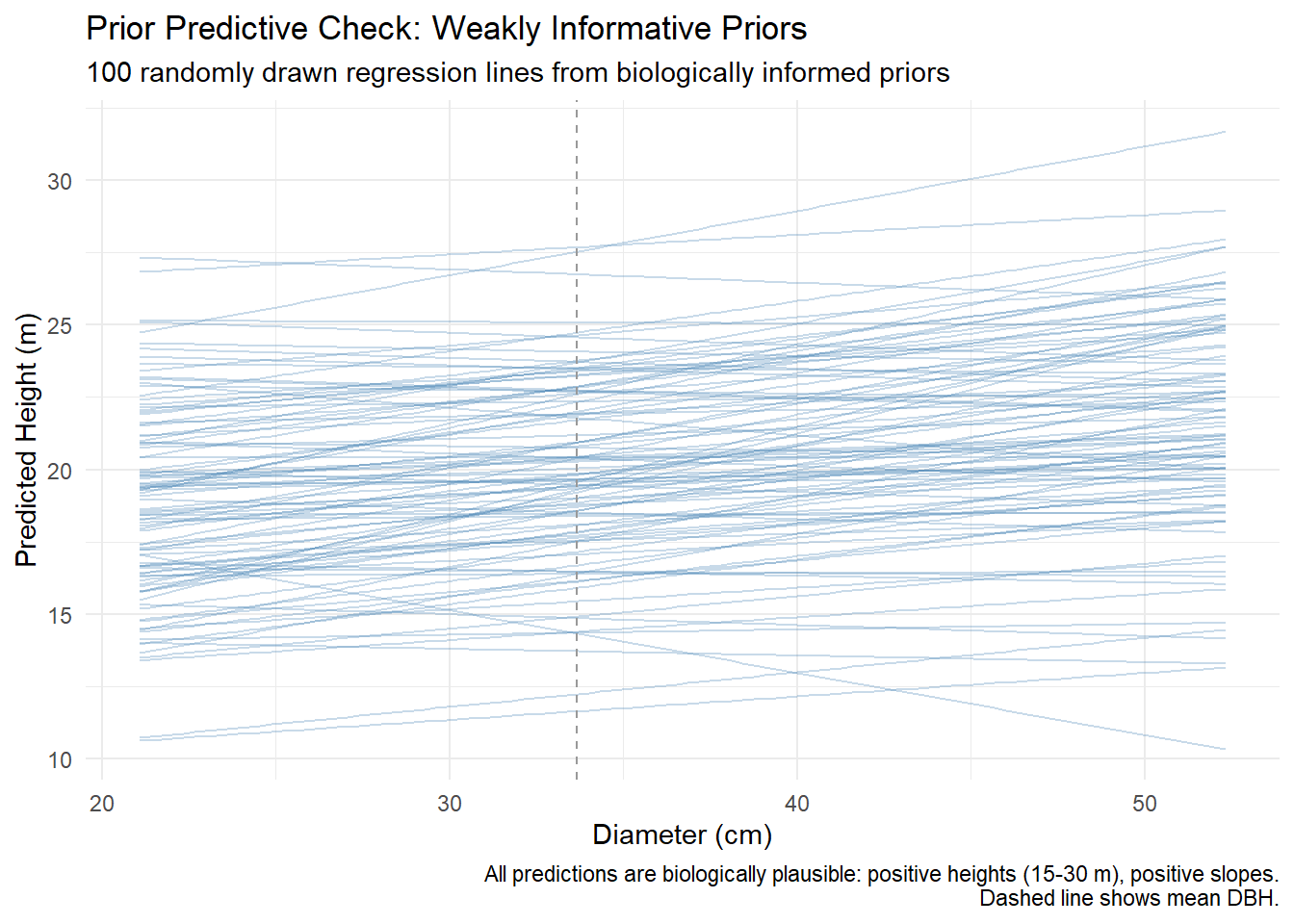

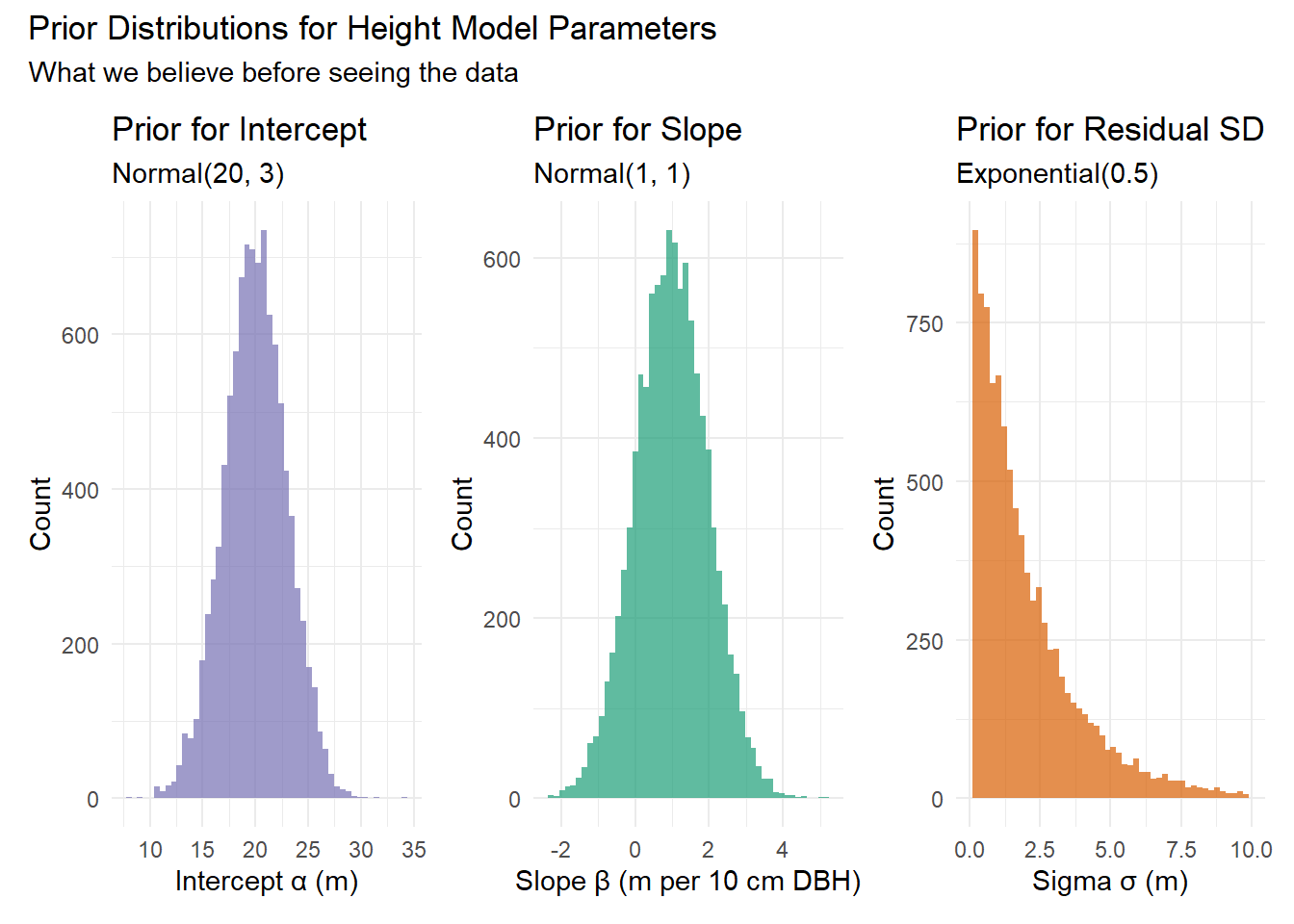

A Bayesian framework naturally handles compound uncertainty by treating each uncertain factor as a probability distribution rather than a fixed assumption:

Instead of: “Assume we achieve 15% deployment”

Bayesian says: “Deployment rate ~ Beta(\(\alpha\), \(\beta\)) based on historical rates across our FMA areas”

Instead of: “Assume costs stay at $3M per decade”

Bayesian says: “Program costs ~ LogNormal(\(\mu\), \(\sigma\)) based on past breeding program expenses”

Instead of: “Assume 2.3% gains translate to field performance”

Bayesian says: “Realized gains ~ Normal(0.023, \(\sigma\)) accounting for site-to-site variation”

Then propagate all these uncertainties simultaneously through the economic model:

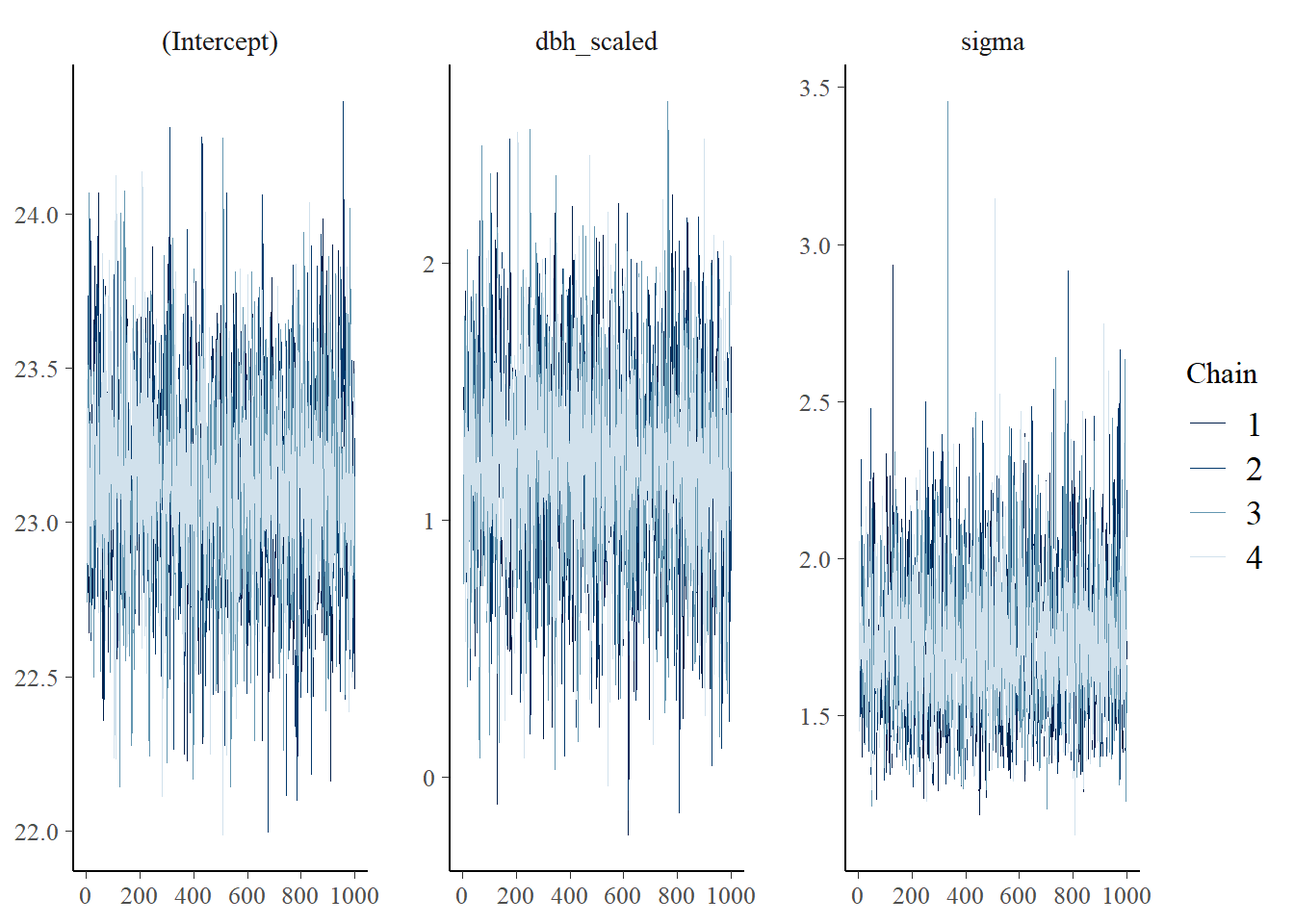

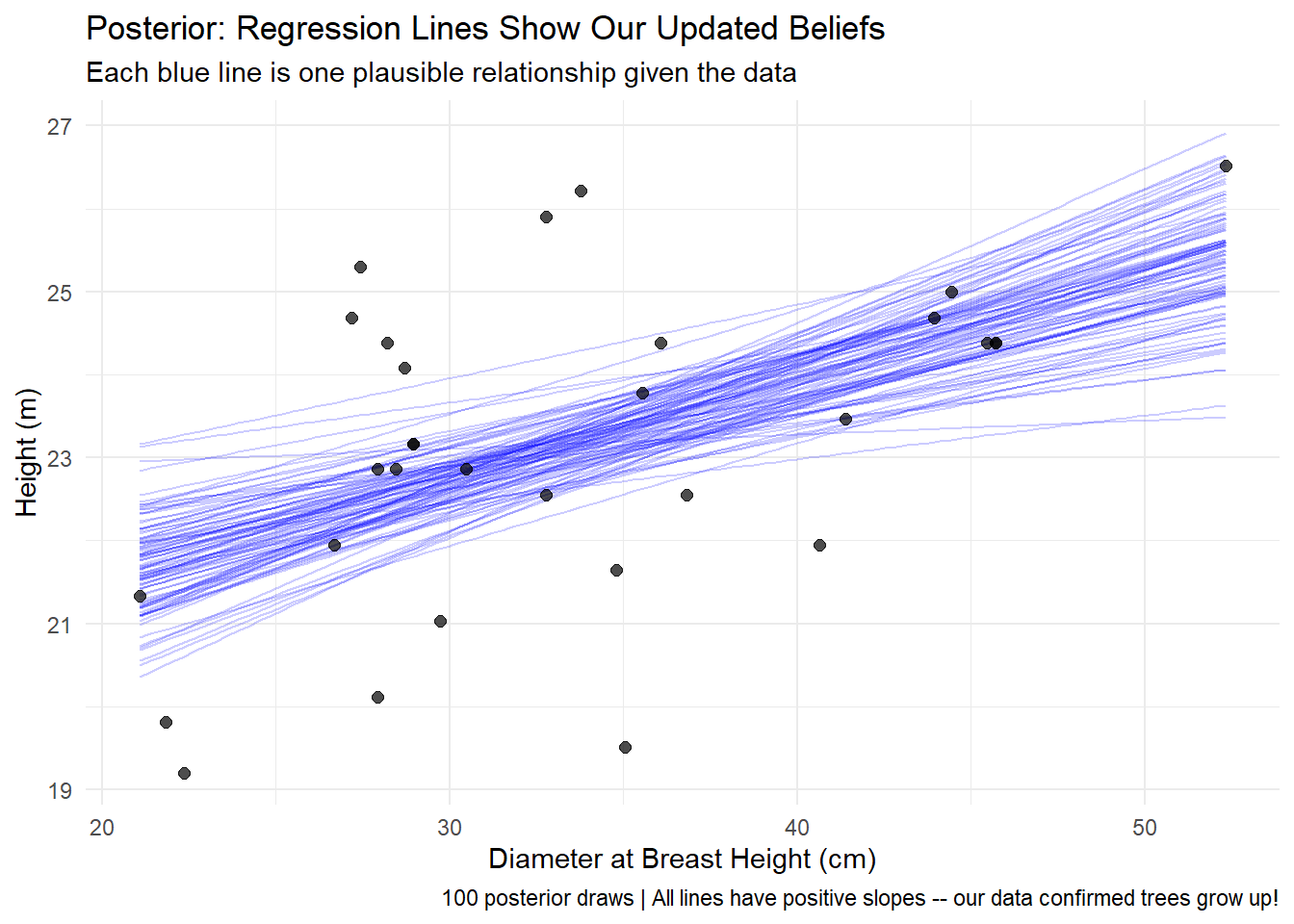

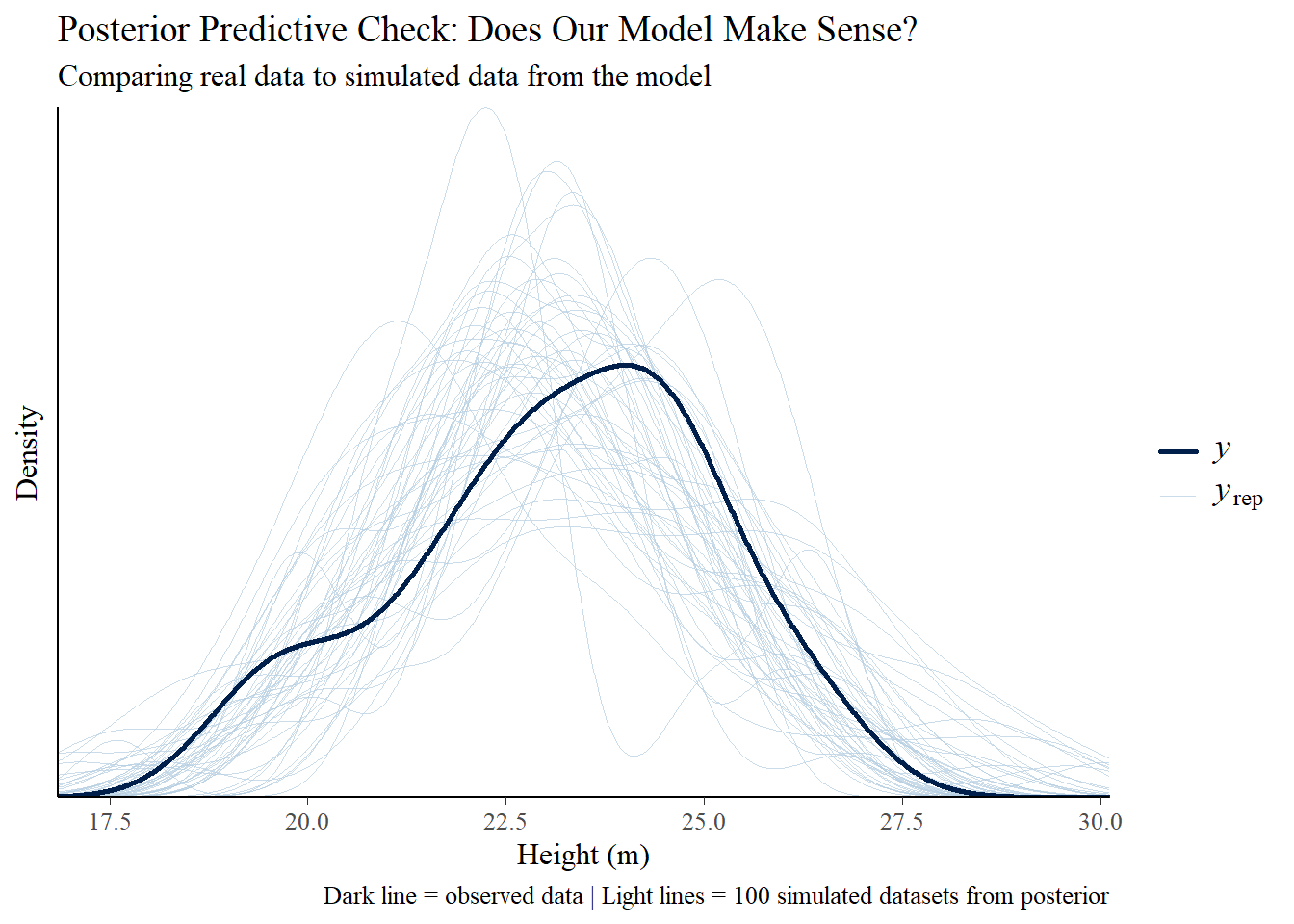

A Bayesian framework handles this the same way we analyzed tree height-diameter relationships earlier in this post: treat each uncertain input as a probability distribution, sample from all distributions simultaneously, and propagate uncertainty through the economic calculation. Instead of running the analysis once with fixed assumptions, you run it thousands of times, each time drawing different combinations of deployment rates, costs, gains, and market conditions from their respective distributions.

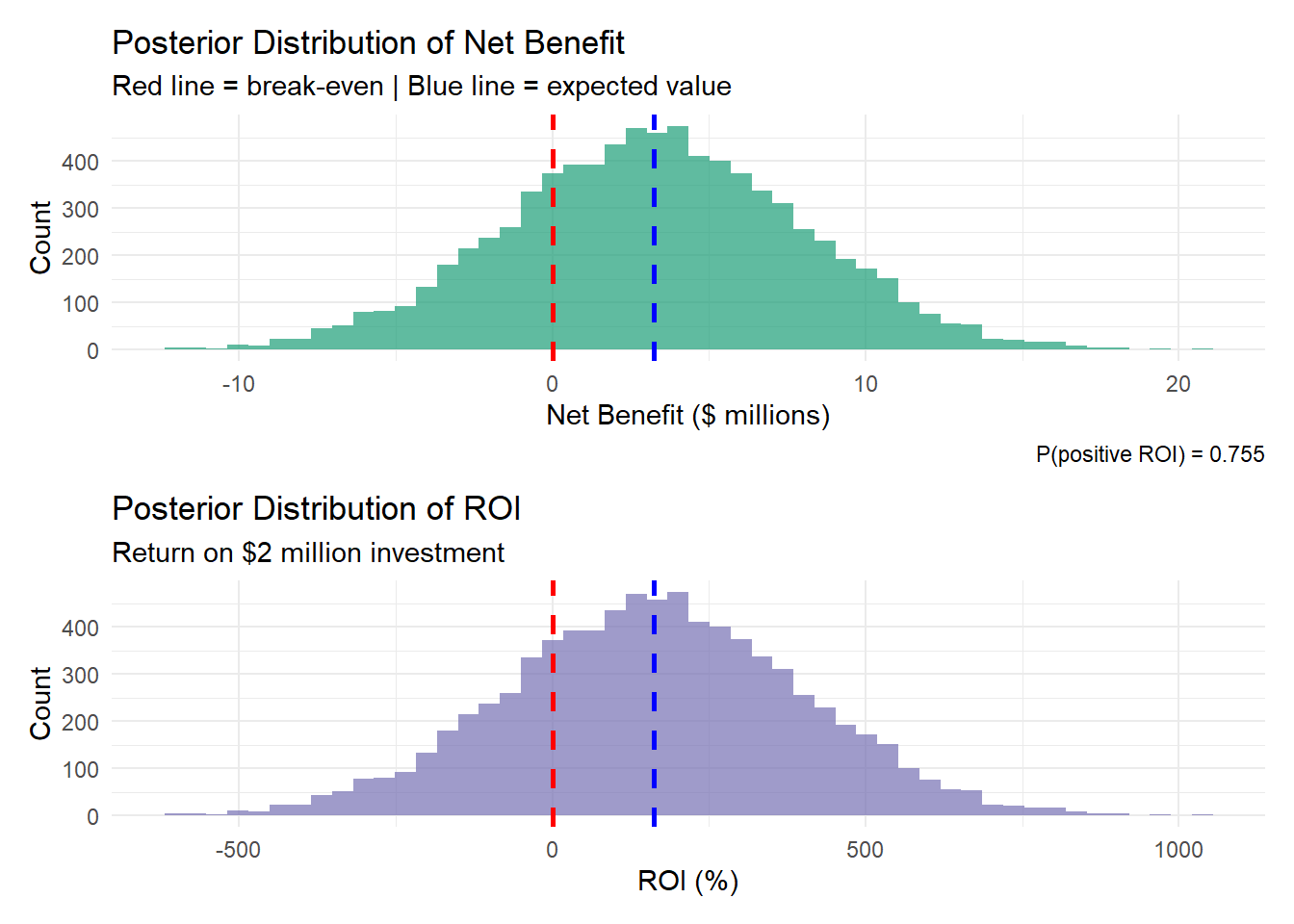

The result isn’t a single number but a full probability distribution of outcomes. Instead of “Expected NPV = $7.4M,” you get probability statements that directly answer the business question: “There’s a 73% chance of positive returns, a 45% chance NPV exceeds $5M, and an 8% chance of losses over $2M.” This directly answers the business question: “What’s the probability this investment pays off given everything we’re uncertain about?”

Schreiber & Thomas (2017) key insight makes it even more important: Deployment area matters as much as genetic gain. In Bayesian terms: If you can control deployment (reduce its uncertainty), you dramatically improve the probability distribution of returns. A company that commits to 20% deployment with high confidence has much better odds than one hoping for 15% but uncertain about achieving it.

Why This Matters

Forest companies face compound business uncertainty when evaluating long-term investments:

Operational uncertainties:

- Can we realistically achieve 15-20% deployment across diverse FMA areas?

- Will field crews consistently plant improved stock rather than wild seed?

- How do deployment logistics vary by terrain and access?

Financial uncertainties:

- Will breeding program costs stay manageable over decades?

- What will improved seedling costs be as production scales?

- How sensitive are returns to discount rate assumptions?

Biological uncertainties:

- Will 2.3% recognized gains translate to actual field performance?

- How much site-to-site variation should we expect?

- Will climate change affect genetic gain realization?

Market uncertainties:

- What will stumpage fees and lumber prices be over 20-year FMP cycles?

- How do mill closures or expansions affect our timber allocation?

This is where Bayesian inference provides clarity. Standard economic models analyze scenarios independently: “If deployment = 15% and costs = $3M and gains = 2.3%, then NPV = $7.4M.”

Bayesian models integrate across all uncertainties simultaneously: “Accounting for realistic uncertainty in deployment (10-25%), costs ($2-6M), gain realization (1.8-2.8%), and markets, there’s a 73% probability of positive NPV and a 45% probability NPV exceeds $5M.”

The critical insight: When only 3 of 7 companies proceed, it suggests the others looked at compound uncertainty and concluded the probability of success was too low. A Bayesian framework makes that reasoning explicit and quantifiable.

Moreover, it identifies which uncertainties matter most. If deployment rate is the dominant factor (as Schreiber & Thomas (2017) suggest), companies can focus on operational commitments that reduce deployment uncertainty rather than waiting for higher genetic gains. A company that can guarantee 20% deployment with high confidence faces much better odds than one hoping for 25% genetic gains that regulators may not recognize.

The Bayesian workflow we’ve demonstrated – specify priors, update with data, propagate uncertainty, make probability statements – applies directly to these multi-million dollar, multi-decade investment decisions where numerous uncertainties compound.

The gap between 2.3% recognized gains and 10-25% demonstrated gains creates a difficult business problem:

- small recognized gains mean economics are marginal, and

- compound uncertainties make outcomes unpredictable.

Only 3 of 7 Alberta programs found the risk-reward balance favorable. Quantifying probability of success under compound uncertainty – rather than analyzing scenarios independently – is exactly where Bayesian methods add value for complex, long-term business decisions.